Everyday life in the institutions

Psychiatry emerged as a health care subject in the 19th century. Special hospitals and nursing homes were built to help people with mental illnesses. Peace and quiet was a key part of treatment, which is why most of these institutions were in the countryside. The isolation justified on the grounds of therapy made it hard for many relatives to visit their sick relations. Patients were also often able to participate little in life outside the institution.

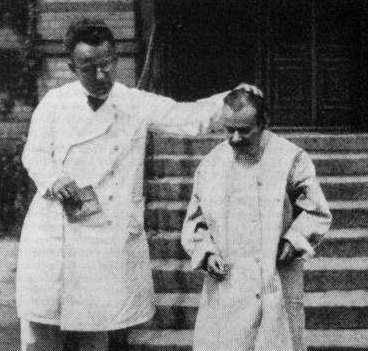

Everyday life in the institutions was strictly regulated, organised and determined by orders and obedience. The medical director was supposed to be the undisputed patriarch of the facility. He had the power to decide on the treatment, discharge and the visiting of patients. He also checked their mail and was allowed to withhold letters.

Many hospitals were overcrowded soon after they opened. Poor hygiene prevailed. Cuts in the hospital per diem charge, staff reductions and a lack supply affected above all patients that were of little interest to the psychiatrists: people whose treatment was futile and whose work performance appeared »worthless«. That is also why cuts in funding for psychiatric patients in the Weimar Republic and under National Socialism triggered little opposition. People who originally expected help in these institutions were mostly entirely at the mercy of this development.

© Verein totgeschwiegen, Berlin, Bildarchiv des Instituts für Geschichte der Medizin, Charité – Universitätsmedizin Berlin